Born in 1953 in Billings, Montana, Shelley Jean Bergum was teaching junior high level special education in Newport, Oregon in 1977 when she sustained a spinal cord injury from a broken back in a car accident and became a wheelchair user. Following her stint in a rehabilitation center in Wyoming, she moved back to Billings for additional rehabilitation. When she returned to teaching in the Billings public schools from 1978 to 1979, she was only allowed to be a teacher’s aide. Although she had a teaching credential and had been a teacher in Oregon, the public schools in Billings said that a teacher had to be responsible for her class 100% of the time, which Shelley supposedly couldn’t do while using a wheelchair. The irony was that she was teaching students who used wheelchairs, and they looked to her as a “roll” model. This was before the Americans with Disabilities Act, and very soon after the passage of Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act, so she had few legal rights and didn’t know about those that she did have that might have protected her.

While in Billings, Shelley met a group of people from the Center for Independent Living (CIL) in Berkeley, which had received a grant to train people with disabilities and parents of disabled children in their rights and responsibilities under the new 504 Regulations. They easily convinced her to move to Berkeley, which she did in 1979. She had a small green Datsun with a big box of a wheelchair carrier on top. The thing had cables and a harness that would drop down and pick up the wheelchair, then lift it up into the box on top of the car. Shelley just drove off on her own, undaunted, to start a new life in Berkeley.

From 1979 to 1982, Shelley worked at the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund, Inc. (DREDF) where she was a trainer and a project manager on a team that traveled around the country to educate people with disabilities about their legal rights and responsibilities. This was the same program that she had attended in Billings and where she met what she called “the fabulous people from Berkeley” who convinced her to move.

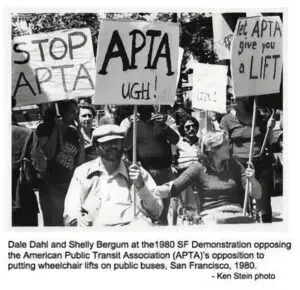

She also planned and participated in the first Disabled Peoples’ Civil Rights Day in October of 1979. This was a big Bay Area event to commemorate the signing of Section 504 of the 1973 Rehabilitation Act, which had happened in April of 1977.

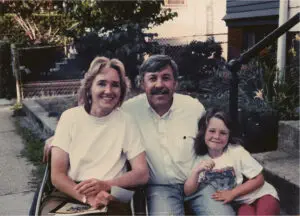

In 1980, while managing a series of trainings, Shelley met her future husband, Marc Krizack, who at that time was a wheelchair mechanic at the University of California’s Physically Disabled Students’ Program. Marc had been hired as the traveling technician for the 504 trainings. His job was to set up and operate the sound system, to make sure the stage was ramped, to take hotel room bathroom doors off their hinges so wheelchairs could fit through, and to fix the participants’ wheelchairs when they broke. Marc would later say that he couldn’t marry the boss’s daughter, so he married the boss instead. In 1988, Shelley and Marc were married, and in 1989 their daughter Ariel was born.

Determined to have a big and lasting impact on the world, Shelley attended Stanford Graduate School of Business from 1982 to 1984, where she got her MBA Degree. For the next 6 years she worked for AT&T in San Francisco in the areas of Marketing and Regulatory Affairs.

In 1990, she was hired by a consumer advisory committee to be the first Executive Director of the California Deaf and Disabled Telecommunications Program (DDTP). This was a State program, the first such program in the nation (now every state has a similar program) that provided free telecommunications equipment and services to people with disabilities. She grew the Program from one employee (herself) to about 70 employees when, in 2002, the State decided to restructure the program and put it out for bid by private contractors.

In response, Shelley formed the California Communications Access Foundation (CCAF) with two other Board members, and in 2003, CCAF won its first competitively bid contract to manage and operate the Deaf and Disabled Telecommunications Program. She grew the Program further from about 70 employees to over 100 in 2014, and bid on and won 4 other State contracts during that period. She also ended the monopoly practice of granting the California Relay Service (CRS) contract to only one telephone company, by awarding multiple contracts simultaneously to promote competition and user choice within the CRS. She was one of the original founders of the National Association of State Relay Administrators (NASRA), which was an education, advocacy and support group for people working in their state’s telecommunications relay services. NASRA worked closely with the FCC to achieve many improvements in relay services for deaf and hard of hearing people, and people with speech disabilities throughout the nation.

Having won the “Flair for Finance Award” as a student at Stanford, Shelley managed to generate a multi-million-dollar surplus, and with CCAF’s Board of Directors, started a program to fund nonprofit organizations in California that were providing services that assist people with disabilities to communicate. Shelley served as the President and CEO of CCAF from 2002 until 2014, when she had to retire due to a severe illness.

Over the years, Shelley served on the Board of Directors and the Friends Committee of the Center for Independent Living and on the Board of Directors of Disability Rights Advocates and briefly until her death on the Board of Whirlwind Wheelchair International.

Although Shelley helped many hundreds of thousands of people through her career and volunteer work, she also quietly helped many individuals in need through significant personal donations. When spare change was beginning to lose its value, she started to give a dollar to homeless people she might encounter while rolling on the street or stuck in traffic on a freeway on-ramp. When questioned that perhaps that was too much to give to someone on the street, her reply was that if she gave $1/day away it would still only be $365 a year – a thought that perhaps we all should remember when encountering someone in great need.

Shelley was committed to social justice. She was outraged by the great disparity in wealth between the highest paid corporate executives and the lowest paid workers. At the time she first mentioned it, corporate executives were earning 240 times what their lowest paid workers were earning. Today that number is more than 400 times.

She was deeply touched the first time she attended a presentation by Veterans of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade, the survivors of some 2800 Americans during the Spanish Civil War (1936- 1939) who traveled to Spain to join the International Brigades to help fight fascism. For years after she donated to them annually.

Shelley always put others ahead of herself. She was never rude, but always complimentary. She never used off-color language. She honored everyone for who they were. Birthday cards for her family arrived a day or two before the birthday, never late. She never missed a special date. She had the highest level of personal integrity one could expect of a human being, even to a fault. She once had a little portable SONY computer system that had become out of date almost as soon as it was made. She was no longer using it, but when her husband asked if he could borrow just the case on a trip he was about to take, she refused, saying that it was purchased by the program and not for personal use.

We often hear about how women have to juggle career and family. Shelley didn’t juggle. She just did everything and she did it all well. She attended all of her daughter Ariel’s PTA meetings and school nights, and when Ariel was sick she would stay home from work to take care of her. She was a loving, responsible, and reliable wife and partner to her husband Marc, with whom she shared a deep and abiding commitment to disability rights, independent living, equality and social justice.

Determined to live her life to the fullest, Shelley will live on in the hearts and minds of those who knew and loved her, and through all that she did to help others and make the world a better place.

Shelley died on January 7, 2016 following a two-year illness.

Shelley Bergum

1953 – 2016

Disability Rights Activist & Leader